I was honored to be asked to compose a post for the Museum of the City of New York's blog this past fall, and to have a chance to mine our collection for material relating to our Mac Conner exhibition, which was on view from September 10, 2014 through February 1, 2015. What a pleasure to work on that show, and to peruse our troves of Stanley Kubrick photographs (explore them here).

I'm feeling nostalgic for these stylish pieces now that they've left us, but I am thrilled that they're journeying across the pond to be seen in an entirely new context: at London's House of Illustration, from April 1 to June 28th of this year.

I've recreated my post below, and you can read the original on the City Museum's blog). And do see the exhibition if you're over U.K.-way!

Illustrator McCauley “Mac” Conner, born in 1913 and still active today at the age of 101, continues to reside in New York City. He arrived during World War II and stayed on to forge his career at a time when the city served as the hub of a burgeoning publishing and advertising industry. From the late 1940s through the early 1960s, Conner enjoyed great success as an illustrator for advertisements and for fiction stories appearing in several women’s and general interest magazines. Mac Conner: A New York Life, on view at the City Museum through January 19, 2015, features over 70 never-before-exhibited original paintings and offers a window into this particular moment of New York City history.

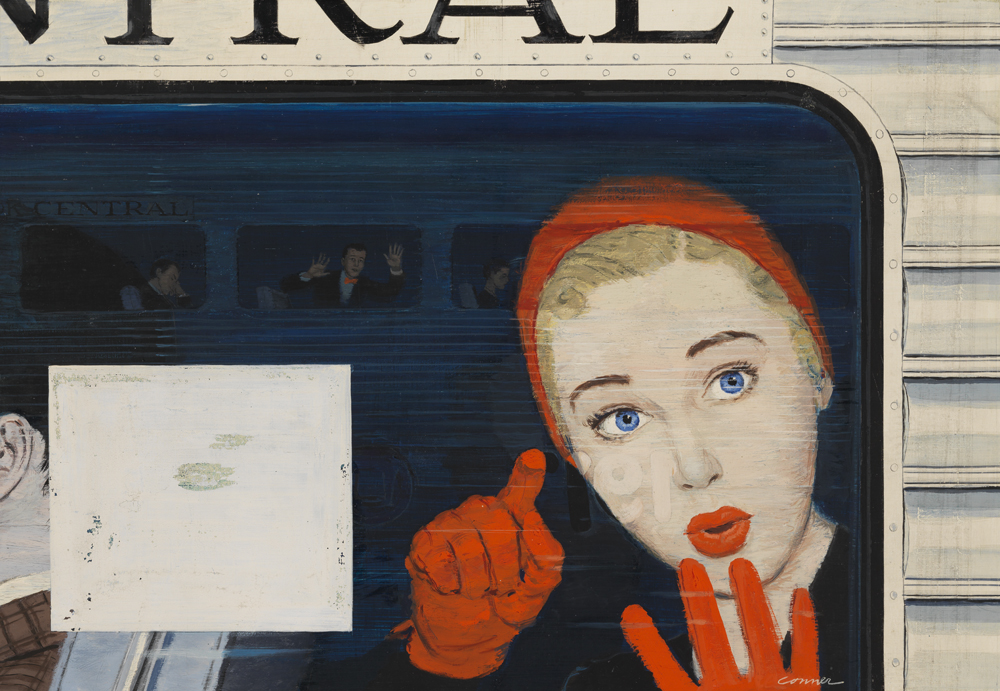

Illustration for "Where's Mary Smith?" in Good Housekeeping, June 1950

Gouache and gesso on masonite

© Mac Conner. Courtesy of the artist

Conner is a keen observer of people, which manifests in the details of gesture and dress that he incorporates into his illustrations. It is this aspect of the process that attracts him, and that he feels distinguishes his work from that of an artist. “I was never interested in landscapes and that kind of thing,” Conner notes. “I was never an artist, in other words. I liked to paint people.” An artist, he explains, “gets a thrill out of painting that tree or that valley. And I never got my thrills that way. I got my thrills from people doing things, the way [a person] stands … they all had their characteristics, and I liked to paint them.”

Illustration for "How Do You Love Me" in Woman's Home Companion, August 1950 Gouache on illustration board

© Mac Conner. Courtesy of the artist

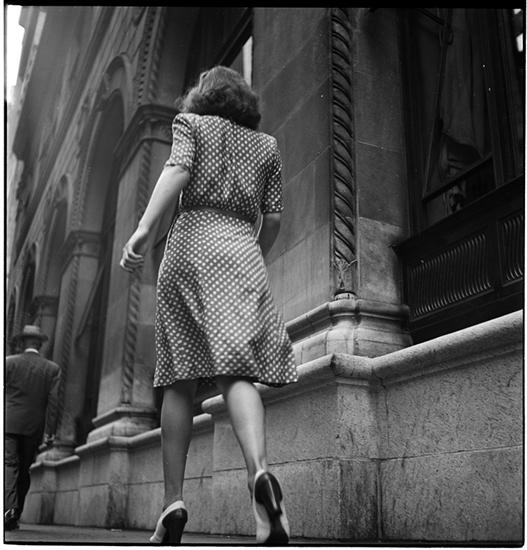

Stanley Kubrick for LOOK magazine. Street Conversations [Woman walking down the street]. 1946.

Museum of the City of New York. X2011.4.10296.50

Conner, like Kubrick, worked on assignment. He was a mainstay illustrator for The Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, and This Week Magazine—a newspaper supplement that at its height appeared in 42 papers nationwide and could have brought Conner an audience of as many as 13 million people. But much of his work accompanied stories published in leading women’s magazines, notably the group known as the “Seven Sisters” (McCall’s, Redbook, Ladies’ Home Journal, Better Homes & Gardens, Good Housekeeping, Family Circle, and Woman’s Day).

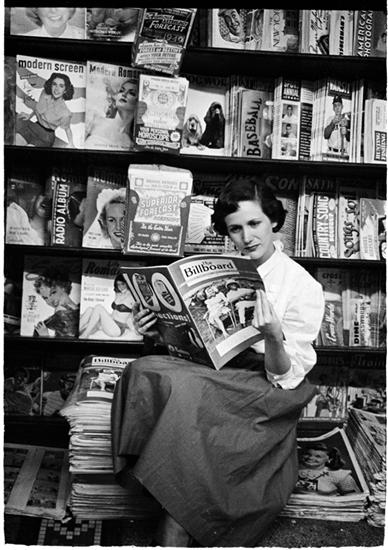

Stanley Kubrick for LOOK magazine. Vaughn Monroe [Woman reading Billboard magazine]. 1949.

Museum of the City of New York. X2011.4.11807.126F

Publications aimed at women were not new; indeed, Good Housekeeping and Ladies’ Home Journal were among those that debuted in the late 19th century. But the proliferation and success of these publications in the middle decades of the 20th century coincided with post-war affluence and an explosion in consumerism—and they provided a powerful boon to advertisers who recognized that women comprised a powerful class of consumers.

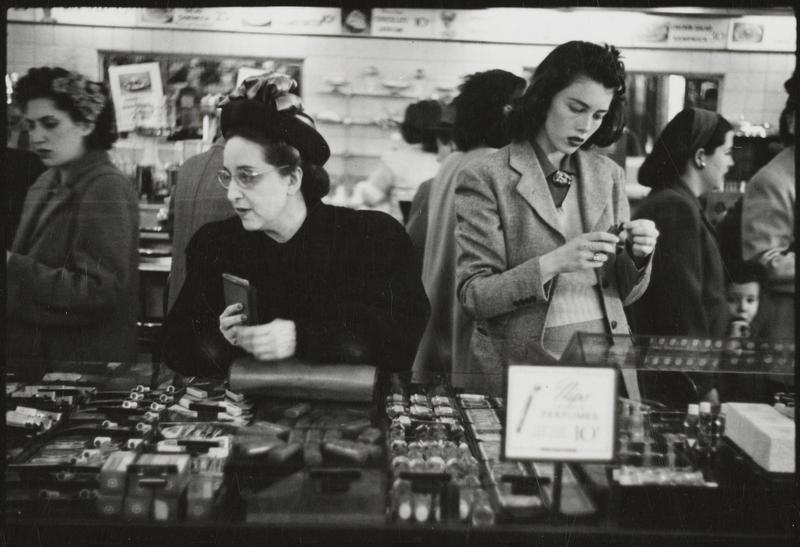

Stanley Kubrick for LOOK magazine. The 5 and 10 [Women shopping at Woolworth's]. 1947.

Museum of the City of New York. X2011.4.10254.25E

Daily life inspired and informed Conner's paintings, which illustrated incidents in fictional narratives. Kubrick found his actual subject in the everyday, generating images that would be published in one of the nation's preeminent photojournalism publications. Conner's paintings reflected cultural trends and mores, whereas LOOK magazine deliberately focused on topical political, social, and cultural issues. Kubrick's photographs from the Museum’s collection, paired with Conner’s illustrations, provide perspective on the atmosphere and style of the times expressed by Conner's imagery.

Illustration for "Let's Take a Trip Up the Nile" in This Week Magazine, November 5, 1950.

Gouache and graphite on illustration board.

© Mac Conner. Courtesy of the artist

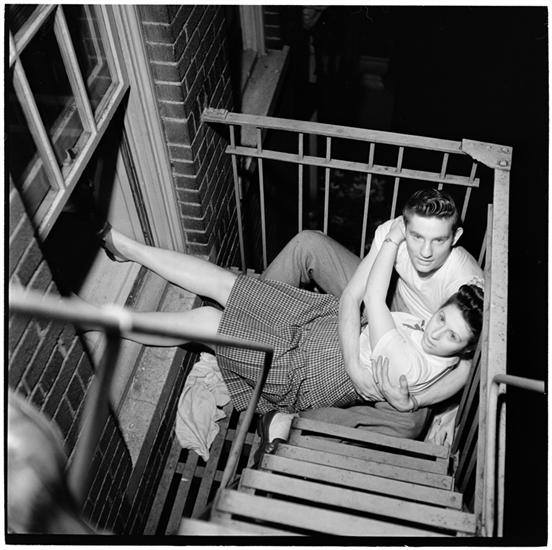

Stanley Kubrick for LOOK magazine. Park Benches - Love is Everywhere [Couple flirting on a fire escape]. 1946.

Museum of the City of New York. X2011.4.10347.11

Conner portrays an idealized, chaste couple in a carefully constructed scene that is likely based on actuality but modified to enhance the overall design. Kubrick explores similar formal devices, such as the perspective from above and the use of angular elements to create a visually interesting composition. But where Conner's illustration permits the viewer to passively observe everyman and everywoman—in essence, offering a representative image of mid-century New York City—Kubrick's lens interrupts and surprises two individuals, intrusively capturing a specific moment in time.

Illustration for "The Girl Who Was Crazy About Jimmy Durante" in Woman's Day, September 1953.

Gouache and ink on illustration board.

© Mac Conner. Courtesy of the artist

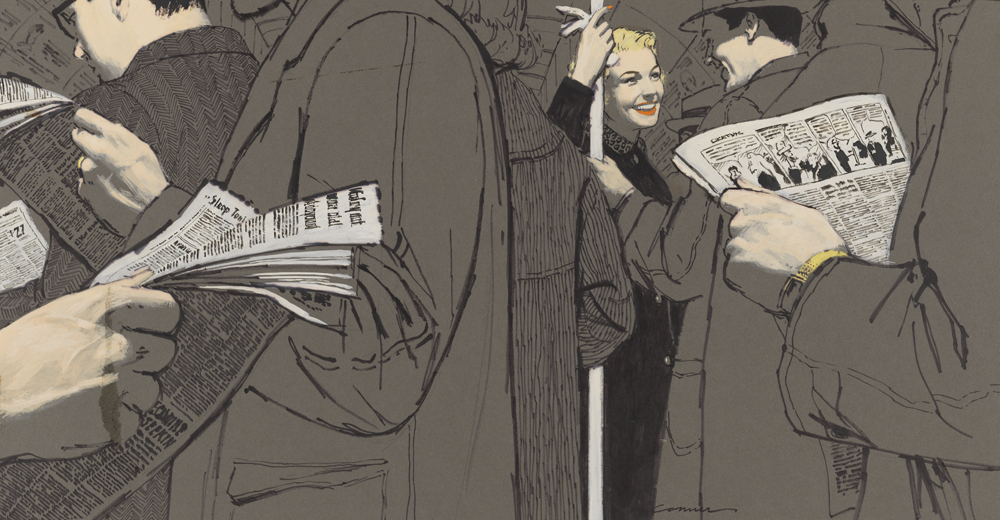

Stanley Kubrick for LOOK magazine. Life and Love on the New York City Subway [Passengers on a subway]. 1946.

Museum of the City of New York. X2011.4.11107.100A

Across from Kubrick sits an attractive, smiling, well-dressed woman next to a man deeply engrossed in his newspaper. Each individual engages with an object or with a person outside the camera's frame; none recognize the voyeuristic presence of the camera/viewer. Conner builds on these components, populating his invented train car with paper-reading gentlemen who convey a sense of quiet rush hour crowds and create a largely gray mass of color that fills most of the canvas. Conner enables the reader to adopt the protagonist’s point of view through this swath of gray-jacketed men and catch a glimpse of the vibrant young lady, fairly sparkling in their midst, who has so captured the narrator's fancy.

Stanley Kubrick for LOOK magazine. People Mugging [Women walking out of a building]. 1946.

Museum of the City of New York. X2011.4.10303.114

Like the girls the narrator describes, the women in Conner’s illustrations are impeccably dressed, icons of contemporary style. He based these details in part on simple observation, but he also cites the influence of his agent’s wife, Jessie Neeley, who kept him informed of changing trends in glove lengths, hairstyles, and the cuts of dresses.

Illustration for "Strictly Respectable" in Redbook, August 1953.

Gouache on illustration board

© Mac Conner. Courtesy of the artist

Conner's depictions of women are reflections of what he saw, but they also set the fashion. Guest curator Terry Brown relates that “it was not uncommon for ladies to go in to a hairdresser, hold out an illustration torn out of a magazine, and say ‘I want my hair to look like that!’” Conner’s women carry purses that match their gloves, display painted nails, and wear the latest fashions, like the wasp-waisted dresses that emphasized the female form and celebrated the end of fabric rationing following World War II. Importantly, his representations offered a model to which women could aspire that was also plausibly within their reach.

Stanley Kubrick for LOOK magazine. Women Trying on Hats [Woman trying on a hat in a department store]. 1946.

Museum of the City of New York. X2011.4.10345.46

These publications were a consumer item that in turn advertised products: everything from home decor and lingerie to food items, complete with recipes and lush photographs of the savory results. But they also sold concepts—of family values, of “American-ness,” of womanhood. While the text in the stories often reinforced predominant stereotypes of appropriate gender roles, Conner’s illustrations imbue his female protagonists with agency. (And women are nearly always his protagonists, even if he portrays a moment when a male character speaks.) The curator in the exhibition text describes this characteristic as “a heightened—but self-possessed—femininity.”

Illustration for "The Good Husband" in Collier's, February 4, 1955.

Gouache and pastel on illustration board.

© Mac Conner. Courtesy of the artist

Kubrick's photographs show stylish women on the street, whose discerning fashion sense informed Conner's work, as well as ladies who frequented stores in pursuit of this seemingly artless elegance. Conner’s is a version of womanliness that fits within the prescribed gender roles of mid-century society while also allowing women individuality, creativity, and power over their self-presentation—a vision that continues to inspire today.

The Museum of the City of New York, located at 1220 Fifth Avenue (b/t 103rd and 104th) is open seven days a week from 10am – 6pm. Suggested admission is $14 for adults, $10 for seniors and students (with I.D.), $3/person for self-guided student groups, and free for ages 19 and under.

Previous post:

Open House NY

2013